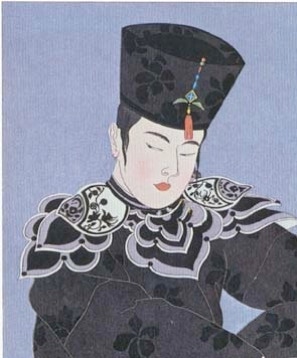

Ming-gwok

Ming-gwok is fictional. He may be the least plausible of the totally fictional characters in The Tale of Murasaki, But he is not impossible. We do know that a group of Chinese were shipwrecked off the coast of Echizen. We know that Murasaki accompanied her father Tametoki when he was appointed governor of that province in 996. We know that a Chinese official by the name of Jyo Shichang led a delegation to escort the refugees back to China. And we know from his reports recorded in the Sung Histories that he exchanged poems with a Japanese official in Echizen. This person was very likely to have been Tametoki. I added the detail that Master Jyo was accompanied by a son. The love affair between Murasaki and Ming-gwok is totally invented. I created it partly to symbolize Murasaki's love of Chinese literature. The Japanese borrowed a great deal from Chinese culture in the centuries before the Heian period, and in so doing they were better able to recognize what was natively Japanese. Cultures lacking a point of reference, an "other" against which to define themselves, typically are unaware of their boundaries as distinct entities. In the same way, having an outsider like Ming-gwok gives Murasaki a chance to reflect on things that otherwise she would have taken for granted.

For example, the fact that upper class women in Heian society were expected to stay sequestered behind screens in the presence of men is shown the scene where Murasaki meets Ming-gwok for the first time. This custom would have been strange to the Chinese.

The poem about the snow seeming like blossoms that Ming-gwok gives Murasaki at their first meeting occurs in her Collected Poems with the simple heading "someone replied." It was the response to the poem Murasaki wrote about the cedars of Hino being buried in the snow.

One imagines Murasaki feeling homesick in Echizen as she wrote:

On the day that my diary said "first snows" I was looking up at nearby Mt. Hinotake, where the snow already lay thick:

Koko ni kaku/ Hino no sugimura/ Uzumu yuki/ Oshio no matsu ni/ Kyou ya magaeru

Here and now/ The cedars of Hino/ Are buried in the snow;/ Today I mistook the scene/ For the pines of Oshio.

Someone replied:

Oshioyama/ Matsu no uwaba ni/ Kyou ya sa wa/ Mine no usuyuki/ Hana to miyuramu

If it snowed today/ On the mountain pines/ At Oshio/ The coating on the peaks/ Would seem like blossoms.

(Richard Bowring translation)

I made Ming-gwok that "someone."

In my book, the scene in which the two talk about their parting is drawn from the chapter entitled "Suma" in the Tale of Genji, where Prince Genji takes leave of his young wife Murasaki before embarking on self-imposed exile-another case of reverse engineering a scene from the Genji tale into the author's life.

When Murasaki sends Ming-gwok a poem about plovers at dawn, entrusting it to the priest Jakusho who travelled to China in 1003, that poem is also drawn from the "Suma" chapter of Genji. Ming-gwok's reply, coming a year later in a box of writing brushes, comes from the "Wizard" chapter of the

Tale of Genji. Genji himself composes it as he gazes at wild geese flying overhead and thinks sadly of his Murasaki who had died the previous year.

The image of the wizard seeking the dead comes from the Chinese poem "Everlasting Sorrow" by Bai Juyi that was so popular among the Heian Japanese literati.

The strange story of Snowball that Ming-gwok relates comes from a collection called Kara Monogatari, "Tales of China," the earliest written copies of which date to the twelfth century in Japan. The tales themselves are even older, so I make the presumption that someone like Ming-gwok would have been familiar with them. In Chinese, the dog's name was "Snow snow."